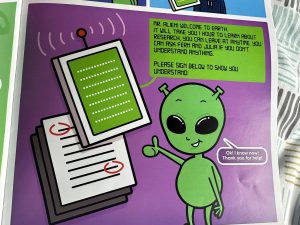

CYCJ are co-developing a young researchers programme for children and young people, with children and young people. The first pilot was led by ‘The Research Racoons’ from Drumchapel High School who carried out an interesting piece of research on ‘Life in Space’. In addition to becoming brilliant young researchers and undertaking this ‘out of this world’ research, they also designed amazing comic books with visual communications experts Meadow Hall and Sarah Ahmad to help explain research to other young people.

Co-production is very often a value-driven endeavour. It often stems from a desire to make the systems and processes by which we ‘do things’ (service design, research, evaluation etc) more equitable, fair and valuable by including those with experience of those systems or processes, the aim being to achieve parity. We agree with Weaver et al. (2019) that user involvement is not only beneficial for the individuals taking part; it increases the effectiveness and credibility of the ‘outputs’ and is central to notions of citizenship and achieving social justice. Many funders, organisations etc. espouse these values and principles, advocating for more ‘lived experience’, increased voice and visibility, and direct decision making and influencing opportunities for those directly impacted.

CYCJ is one of those organisations. Participation directly is embedded in our organisation, through our participation strategy and work strand. #TeamResearch is no different. We’ve been using, developing, and promoting best practice around ‘child-friendly’ research and methods. And we’re committed to taking this a step further, through designing and developing with children and young people a ‘young researcher programme’. The programme will enable children and young people to engage with the skills, knowledge and understanding required to undertake and lead social research which is both rigorous and ethical. By sharing our research skills and knowledge with children and young people we can co-design and develop tools to support and encourage other children and young people to undertake social research.

While many funders and organisations promote the principles of co-production, it can feel our systems and processes are yet to catch up with the flexibility and adaptability that’s required. For example, we need processes to ‘pay’ our young researchers as we would with any other collaborator or colleague. We need ethics committees to take a broader view of the ethical implications of this type of work, beyond institutional risk. We need those who give us the green light to also allow a degree of flexibility in terms of plans, timelines, spend and outcomes. Often what gets these projects over the line successfully requires thinking outside the prescriptive boxes of proposals and project plans. So, after piloting parts of the young researchers’ programme, what are our reflections?

One of our key reflections from the young researchers’ programme is the importance of time. Like all good participation work, co-production requires time; time to build relationships, to be flexible to the needs of the group, and to ensure that avenues of communication can remain open after specific pieces of work have been completed. We approached the programme with the mindset that the group had power to make decisions about how we would conduct research together, and what this research would explore. Whilst we dedicated part of the programme to learning about the fundamentals of research, we really wanted the entire experience to be adaptive, engaging, and driven by what motivated the group. This meant that we (on more than one occasion) went off-piste in several directions, from exploring famous scandals in research ethics to landing on our final research topic of extra-terrestrial life. You can do all the planning you like, but if a session doesn’t land, takes twice as long, or the project takes a whole new direction you need to think on your feet, adapt the plan and develop a new set of ideas, activities, and resources – all in time for the next session.

In addition to our research topic being a bit larger than expected (i.e. as big as the galaxy), we also had more young people sign up to the programme than we had anticipated. This was a blessing to us of course, but it changed the expected dynamic of the programme from a small, focused research group to a coming together of a whole range of interests, experiences, and perspectives. This change in dynamic required a change in pace: simply put, we needed more sessions over a longer period of time. Working for a longer period of time, we developed strong relationships with the group, and the young people developed a cohesive collective identity. Our flexible approach to the programme meant that we were able to adapt to these changes, but there were some hurdles to cross along the way. With a limited budget and time constraints outwith our control, our adaptability was less than what would have been ideal. We found ourselves scheduling additional group sessions and crunching numbers to make sure our Research Racoons had all of the snacks required to fuel their hard work. In addition to this we also had boundless support from the school’s resident youth worker Ally, who went above and beyond to make it work, helping bring together the young researchers and supporting the organisation of our sessions.

On reflection, all of these challenges, surprises, and changes encompass a lot of the key ingredients of co-production with children and young people: the need for flexibility, the openness and willingness of the ‘gatekeepers’, the time and space to develop trusting relationships, and ultimately a balance of power. All of these factors came together to create an environment that was engaging, dynamic, and mutually beneficial. Using our more ‘traditional’ evaluation measures – ‘completed on time, in budget, with all planned outputs’ – it might have appeared the project went awry. In resisting the opportunity to take the reins we created a space (get it 😉) in which the young people ‘felt like they had genuine control and ownership’. Our role, then, became to hold the space, which meant they could ‘ask silly questions and make mistakes’, as this was part of our learning together.

Unsurprisingly the young people thought the programme could be improved by ‘having more time’ and with this we wholeheartedly agree. More time wouldn’t necessarily have led to more work being undertaken, or changed the outputs we developed, but would have given space for more of the bits that actually matter: building relationships, trust and friendship; having fun; becoming a team; testing ideas; failing; and being creative.

So, while there is commitment to the principles of co-production, this isn’t necessarily reflected in the processes by which this type of work gets funded or operationalised. And in addition to changing the direct practice we need to shape these as well. We’d recommend that fundings and timelines are flexible when undertaking this type of work with children of young people; we feel that a good understanding of participation from those in leadership positions will help support this change.

About the authors: Fern Gillon is a Research Associate and Julia Swann is a Participation and Policy Advisor within CYCJ.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.